(My entry on the historical context of team orders is three weeks overdue. This was supposed to be it, but the subject covered here on closer examination seemed to justify its own entry.)

The oft quoted example in the history of team orders is when during the last race of 1956 at Monza, Peter Collins handed over his Ferrari to team-leader, Juan Manuel Fangio, despite Collins still having a shot at the title himself. Fangio won the title by three points over Stirling Moss (competing for Maserati), and five points over Collins. However, Moss had already lost the title by Monza. It was a matter of which Ferrari driver would take the ‘Championship with a team-decision taken that the Maestro was the prefered choice, not a situation of handing Collins’s car to Fangio as the team deemed he had a better chance of beating Moss to the prize.

Juan Manuel would have been the preference of the marketing department, and whilst that description would have been unknown, marketing, as in the saying of the time, “Win on Sunday, sell on Monday”, was part of motor-racing. Fangio had won in 1951 with Alfa Romeo, 1954 and ’55 with Mercedes, and was certainly the star-name. More than that, driver-hierarchy, especially in factory teams and most especially at Ferrari, in those days could be very rigid. It was not unknown for a team to enter a junior driver just so he could be called in and hoicked out if one of the senior names had a problem with his own vehicle. From 1950 to 1957, points for shared drives were split, half-points if two drivers, a third of the points each if three drivers. From 1958, shared drivers were permitted but did not count for points. I am not sure when shared drives were banned altogether (please comment if you know). The last example I can find is the penultimate round in 1964 at Watkins Glen (USA) when Jim Clark dropped from the lead with fuel-injection problems, then swapping cars with Lotus team-mate, Mike Spence. Clark almost caught his title rivals, John Surtees and Graham Hill, in the hope of passing them to reduce their points, but a fuel-pump problem saw him fall back again to seventh/retired.

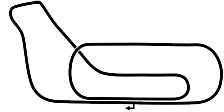

The scoring system in 1956 was 8-6-4-3-2 plus 1 point for the fastest lap, with only the best five results from seven rounds (ignoring the Indianapolis 500) counting. Before Italy, Fangio had 30 from five scoring results, the worst of those being four points for third in France and Monaco, so he had to finish first or second to improve his tally. Moss had 19 points from five results, only had to improve on single-point scores from France and Britain, but could not win the title. Collins had 22 and did not need to worry about dropped scores, so if Fangio failed to improve his score at Monza, he could win the title with the eight points for a win on countback, or outright if he also took fastest lap. The race was held on the double-clockwise 6·21 mile (10 km) road-course/banked-oval configuration (in which the two straights in front of the pits were one wide straight separated by some cones or the like).

The scoring system in 1956 was 8-6-4-3-2 plus 1 point for the fastest lap, with only the best five results from seven rounds (ignoring the Indianapolis 500) counting. Before Italy, Fangio had 30 from five scoring results, the worst of those being four points for third in France and Monaco, so he had to finish first or second to improve his tally. Moss had 19 points from five results, only had to improve on single-point scores from France and Britain, but could not win the title. Collins had 22 and did not need to worry about dropped scores, so if Fangio failed to improve his score at Monza, he could win the title with the eight points for a win on countback, or outright if he also took fastest lap. The race was held on the double-clockwise 6·21 mile (10 km) road-course/banked-oval configuration (in which the two straights in front of the pits were one wide straight separated by some cones or the like).

After Castellotti and Musso had used up their tyres squabbling for early first position and had to pit, Moss, Fangio, Collins and Schell were then in the lead slipstreaming group. Near half-distance, Fangio pitted his Lancia-Ferrari with a damaged steering arm. The car was patched up and sent out again, but with Castellotti (having crashed earlier) at the wheel. It eventually finished eighth, 4 laps down, but after the delay of repairs, was of no use to Fangio, needing as he did at least second-place to improve his score. Moss was pulling away at the front, Musso’s Lancia-Ferrari moved up to second when Schell pitted for fuel, and then Musso pulled in to refuel, the car not being handed over to Fangio as many expected. (Maverick points out in the comments that Musso refused to hand his car over.)

At this stage, Fangio could only add to his ‘Championship score by getting a team-mate’s car, winning the race for four points for a shared win, plus gaining the extra point for fastest lap to make five points, improving his score by one with having to thus drop one of his four-point scores. Of course, had Fangio won with or without the FL, it would stop Collins getting the victory to win the title. Collins meanwhile was in a position to win the race and title if Moss had any sort of problem. With fifteen to go, the team called Collins in for a ‘tyre check’, and then put Fangio in the car. At this point, Fangio was World Champion, and Collins was not. Moss had a scare when his Maserati ran dry, was nudged back to the pits by team-mate, Luigi Piotti, losing the lead to Luigi Musso, but regaining it when the Italian driver had a steering-arm failure. Stirling won with the fastest lap, scoring the maximum nine points, albeit only improving his total by eight to 27, because of having to drop a one-point score. Juan Manuel scored three for a shared second-place with Collins, but remained on thirty points, as the 3-point haul became his dropped score. So Moss scored the maximum points he could, Fangio scored none towards his total, and still became World Champion. Peter Collins also got three for the shared second-place, pushing his account up to 25 for third behind Fangio and Moss.

At this stage, Fangio could only add to his ‘Championship score by getting a team-mate’s car, winning the race for four points for a shared win, plus gaining the extra point for fastest lap to make five points, improving his score by one with having to thus drop one of his four-point scores. Of course, had Fangio won with or without the FL, it would stop Collins getting the victory to win the title. Collins meanwhile was in a position to win the race and title if Moss had any sort of problem. With fifteen to go, the team called Collins in for a ‘tyre check’, and then put Fangio in the car. At this point, Fangio was World Champion, and Collins was not. Moss had a scare when his Maserati ran dry, was nudged back to the pits by team-mate, Luigi Piotti, losing the lead to Luigi Musso, but regaining it when the Italian driver had a steering-arm failure. Stirling won with the fastest lap, scoring the maximum nine points, albeit only improving his total by eight to 27, because of having to drop a one-point score. Juan Manuel scored three for a shared second-place with Collins, but remained on thirty points, as the 3-point haul became his dropped score. So Moss scored the maximum points he could, Fangio scored none towards his total, and still became World Champion. Peter Collins also got three for the shared second-place, pushing his account up to 25 for third behind Fangio and Moss.

The myth is that Collins heroically handed his car over to Fangio so the Argentine could beat Moss to the title with the points he got for shared second. This is clearly bunkum (to put it politely). At the time of the race I am sure that it was realised Moss could not mathematically win the title, even if dropped scores can confuse some people. I contend this idea that Collins, in this great sporting gesture, was helping Fangio to win the title over Moss was added to the legend later on, by those that could not credit that the Ferrari management would simply do it to make one driver, and definitely not the other, World Champion, and without checking the arithmetic, beyond seeing Fangio scored three points in that race, and won the title by two. Furthermore, I do not buy that Collins volunteered his car to Fangio. In those days, the media were far more likely to accept what they were told, unlike the modern press corps that question unrelentingly anything they may have reason to doubt. Why would Ferrari bring Collins in for a tyre-check? It was certainly a period when the team’s concern for driver-safety was only conspicuous by its absence. The way they would have checked the tyres would be to leave the car out and see what happened. Just as more recently Massa was supposed to let Alonso by without revealing he had been told to, I believe Collins had to come in, had to hand over the drive, and then explain it was his decision to reporters, who might have had their own doubts, but would relay what they were told. I would be willing to bet good money, and plenty of it, that when the Brit bought his Ferrari in, Fangio was on the spot immediately ready to jump in, and did not need to be called over to need persuading that due to an entirely unexpected, spontaneous, magnanimous gesture on Peter’s part, the car, and title, was his to take.

August 9, 2010 at 10:11 PM |

I had no idea car swaps happened as late as 1964 or that Jim Clark had ever benefitted from such a thing.

The press in 1956 would have had no problem with a team telling a driver to hand over his car to a team leader. With modern eyes it is odd but then it was normal. You only have to look back to Imola 1982 to see the reaction to Pironi taking the win from Villeneuve when he had been given team orders to do so and had a clause in his contract that he was not allowed to compete with Gilles. Now it would be seen as a team interfering with the natural outcome of the race but complying with team orders to give up a place or a car was normal.

August 10, 2010 at 10:25 PM |

As we both know, this was a period when Jim Clark in his Lotus-Climax was usually fastest, generally winning or breaking down, with reliability the deciding factor on his title-wins in ’63 and ’65, or title-losses for other years in this period. Bearing in mind the other Team Lotus drivers that season, Peter Arundell for four rounds then Mike Spence, between them took only one point off Hill and nothing off Surtees, I am surprised that the tactic of calling them in to hand the car over to Clark, to at least give the Scot the chance to take points off other title-contenders even if unable to score himself, was not used sooner than somewhat of a late effort at Watkins Glen to keep Clark’s title-hopes more alive, or indeed not used in previous seasons. Thus far that season, Clark had won three, finished 4th after breaking down late, and had four other mechanical retirements before the USA GP. Even though Hill did win with Surtees second, Jim Clark still had a mathematical chance at the last round, but needed to win with Hill lower than third and Surtees lower than second. Unfortunately, another mechanical problem left Clark fifth in Mexico, Hill did not score, Surtees was second, so if Clark’s engine had hung on another couple of laps, he led the first 63 of 65, he would have won the title equal on 39 points with Hill on countback, four wins to two (if that was the tiebreak and not that Hill had 41 but had to drop his seventh-best score of two points (in the event those two dropped points gave the title to Surtees with 40 points)).

August 10, 2010 at 4:12 AM |

That was a really enjoyable read; I love the history of the sport and am surprised to hear that team orders went on so long ago, no wonder that Ferrari find it difficult to conceive that there is anything wrong with manipulating the result in favour of their preferred choice.

Did Collins remain in the team after that incident do you know? It would seem to have been the ultimate slap in the face after all his hard work.

August 10, 2010 at 5:52 PM |

Peter Collins did remain with Ferrari. He died after an accident in the 1958 German GP, two rounds after Luigi Musso, still with Ferrari, was killed in the French GP. That was the year Mike Hawthorn won his title with Ferrari.

August 10, 2010 at 9:01 AM |

“…and then Musso pulled in to refuel, the car not being handed over to Fangio as many expected.”

Musso refused, hence the myth about Collins.

August 10, 2010 at 5:42 PM |

Thank you for the information. I have added it to the entry. I doubt that decision did much for Musso’s status in the team concerning getting the best equipment and backing after that.